Improving Police Leadership and Enhancing Community Safety Across America

- A Griffin Catalyst leadership gift of $25 million has supported the establishment of the Community Safety Leadership Academies, which include both the Policing Leadership Academy (PLA) for officers in key leadership positions, and the Community Violence Intervention Leadership Academy (CVILA) for community-based violence prevention professionals.

- Recognizing the importance of professional development for the captains and commanders charged with keeping communities around the country safe, the PLA gathers mid-level police leaders—the next generation of chiefs and superintendents—from around the country for an intensive five-month management and leadership training program.

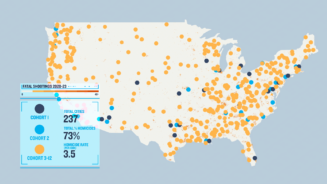

- In November 2024, the PLA graduated the latest of its first three cohorts, representing a total of 95 police leaders from 64 localities where, collectively, 30% of all homicides in the United States are committed annually. This ambitious new model of training is being rigorously evaluated through a randomized controlled trial, to determine the impact of this investment on reducing violent crime, improving officer wellness, and increasing police-community trust.

The Crime Lab and its partners have made the communities they serve safer. The success of these programs demonstrates that we know how to better protect our residents and build stronger bonds between law enforcement and our neighborhoods. Leveraging these insights, the Police Leadership Academy will bring together the best minds from policing and law-enforcement research to strengthen the way we invest in community safety.

Public safety is the foundation of a healthy community. If a neighborhood is not safe, every other aspect of its people’s lives—educational achievement, employment opportunities, health outcomes—suffers. Dramatic disparities in life expectancy between wealthier, secure communities and poorer, often dangerous ones—as much as 30 years in some cases—speak to the vital role of safety in public spaces.

Building on a simple but powerful premise—that we should train and invest in the professional development of police leaders much as we train and invest in rising business leaders—the Policing Leadership Academy (PLA) aims to improve public safety in cities and towns across America. This initiative is a vital part of Griffin Catalyst’s efforts to support vibrant communities and to enable individuals of all backgrounds to pursue their dreams.

The new PLA is a direct outgrowth of the Crime Lab’s success in 2016 and 2017 in working with the Chicago Police Department to stem a crime surge in some of Chicago’s most historically violent neighborhoods—while simultaneously working to build public trust in policing itself—using a combination of new management strategies and data-driven decision making.

This success was consistent with the experience of America’s two largest cities, New York and Los Angeles, which saw their homicide rates drop by an astonishing 80% and 50%, respectively, in the space of a decade or less. This progress was credited, in large part, to enhanced leadership, data-driven policing strategies, greater accountability, and higher performance expectations in these departments.

While it has been hypothesized that improvements in police management can drive these meaningful improvements in public safety, in March 2022 new research proved just how promising this proposition was for reducing violence across the country. Crime Lab founder Jens Ludwig, Max Kapustin of Cornell University, and Terrence Newman of the University of Texas published new work finding that improved management alone could dramatically and swiftly raise the quality and positive impact of police departments across the nation.

While both this research and the experiences of New York and Los Angeles show what is possible, few of the 18,000 police departments in the United States have the resources or infrastructure to implement these strategies, invest in their rising leaders, or provide ongoing, targeted, and world-class career development for their officers.

What if a new, national police leadership academy could fill this void for our nation’s 18,000 departments? This new concept would enable commanders from around the country to receive the kind of management training common in business, education, healthcare, and other sectors.

Creating Safer Communities by Improving Policing

Corporations spend billions of dollars to further educate their employees. They send them to Sloan School of Management at MIT; they send them to Harvard Business School; they invest in professional development. Government is woeful in that regard. In police departments, you learn what you learn; you learn from the other people; you get promoted; now get to work. So the training of police management is critically important. Because it’s a different job than a patrol officer. A captain is not generally chasing 911 calls. They’re not usually actively engaged in shootouts. It’s a management job. You are in charge of people.

To transform its vision into reality and to expand a promising local effort into a successful national—or even global—one, the Crime Lab turned to Griffin Catalyst, which has long been focused on improving safety in communities across the United States.

In May 2022, Ken Griffin announced a leadership gift of $25 million to support the creation of the Community Safety Leadership Academies, consisting of the PLA and a complementary program, the Community Violence Intervention Leadership Academy (CVILA), designed to train non-police professionals on the front lines of public safety.

For five months, including one week per month in person at the academy in Chicago, PLA participants would receive instruction from policing and management science experts, work together on data-driven strategies, and prepare an individualized capstone project to tackle a challenge in their home community—a kind of senior thesis—they could continue after the program.

To construct its curriculum, the PLA turned to some of the most respected police professionals in the country. “The biggest names in American policing said yes to this and signed up right away,” Roseanna Ander observed.

Senior advisors to the project included Bill Bratton, legendary commissioner of the New York, Boston, and Los Angeles police departments; Constance L. Rice, the renowned civil rights activist and lawyer; and several senior officials from the U.S. Department of Justice—all of whom recognized the importance of the effort and were eager to participate.

In May 2023, the PLA’s first cohort arrived in Chicago: 25 commanders representing 24 localities, from America’s biggest urban areas to small towns and rural areas to Native American tribal nations. “We use the term ‘commander’ as kind of a catchall,” explains Meredith Stricker, the PLA’s executive director. “It could be a captain, even a deputy chief, but ‘commander’ is the most common phrase in American policing. Our LAPD officer had close to 300 officers reporting directly to him; that’s the force of a decent-sized city, right? Our New York person had close to 200. And we’ve got two tribal nations, including the Navajo Nation.”

Participants received intensive instruction from professors at the University of Chicago—including from the Booth School of Management, the Law School, and the Harris School of Public Policy—along with a wide range of practitioners and leaders. Subjects ranged from departmental management to “precision policing” based on the use of data and technology.

Much of the learning came the participants themselves. Because the PLA included only one officer from each locality, commanders could speak candidly with peers. “We’ve created a space where they can be really honest about what’s not working, what they’re frustrated with, what the challenges are in their department,” Meredith Stricker observes. Some called it the “peer network;” others referred to the “cohort fffect.”

The collective knowledge and experience of the first PLA cohort was upwards of a thousand years, all in one room, and that is astonishing. Being a part of the PLA allows me to access the cohorts’ collective knowledge to address the challenges we face at home. It allows me to make a call to my peer in Los Angeles or New York and find out how they are addressing a problem, and determine if their approach would work in my jurisdiction, or could be adapted so that it does.

By November 2024, when the PLA graduated the most recent of its first three cohorts—a total of 95 officers from 64 localities where, collectively, nearly one-third of all homicides in the United States are committed annually—it was obvious the program was achieving impressive qualitative results. “One big-city commander said to us on Day Three, he had learned more in three days than he had learned in all the trainings he had ever received in policing up until that point,” Meredith Stricker recalls.

But would the PLA make a quantitative difference in police performance in America? As an integral part of this effort—and with the support of Griffin Catalyst—Max Kapustin and his colleagues have begun a rigorous study on the impact of the PLA, through a series of randomized controlled trials. “We wanted to make sure that as we jumped in with both feet to do something in the immediate term,” Roseanna Ander noted. “We were generating evidence to document and learn as much as possible while we were doing it.”

If we get this strong evidence for [improved police performance], you can imagine it beginning to change the conversation on how much we invest in police training and make us a bit less of an outlier compared to our peer nations. If the idea really had legs and evidence and data behind it, you can imagine changing the entire landscape of how we train police in the United States. I think that's a real possibility.